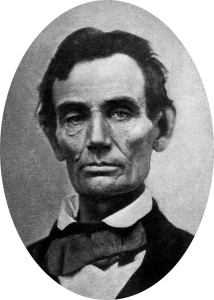

- Lincoln in 1858.

In which we see that even old people have heroes.

Emily.

—Mr. K.

The other day you referred to Abraham Lincoln as “my boyfriend.”

—I did.

Can I infer from this that you have some curiosity about our relationship?

—Hey, whatever you’re into, Mr. K. You do have a wedding ring, I see.

I do.

—But what you do on your own time is your business.

Agreed. Of course your observation about my wedding ring testifies to your powers of observation—and can be taken as an ongoing indication of your curiosity about the status of my relations with Mr. Lincoln.

—Are you married to him?

—OK, this is officially weird.

Well, making you uncomfortable is not the goal here, Sadie. What I’m really trying to do is leverage Emily’s interest for larger pedagogical purposes. That’s why I’m appointing her chief interviewer. Emily you’re going to be the Director of Information Management on Abraham Lincoln for Mr. King’s US History Class. Your fellow students are your staff members. Fire away.

—Uh. OK. This is officially weird. But whatever. First question: are you named after him?

Yes. But your job is to ask about my boyfriend, as you refer to him, not me. Though you may learn about me in the process.

—You’re named after him? That’s so cool!

You might say my father was also Abraham Lincoln’s boyfriend, Kylie.

—Let’s stop with this analogy. But was your dad a teacher too, Mr. K.?

No, Sadie. Just a passionate lover of history. But let’s keep our focus on Mr. Lincoln.

—Right. So tell us about Abraham Lincoln. He wasn’t actually born in a log cabin, was he?

Pretty much. The exact circumstances of Lincoln’s birth are unclear, but his basic circumstances are well-established: he was born poor in Kentucky. His beloved mother died when he was nine years old. His beloved sister died when he was a teenager. He didn’t get along with his father. His family moved from Kentucky to Indiana, and later to Illinois.

—What kind of kid what he?

A little strange: He liked to read. Which is surprising, since he received about a year, total, formal education. His father, among other people in his extended family, thought he was lazy. But Lincoln was lucky: his dad remarried after his mother died, and—contrary to the fairy tales—his stepmother proved to be a godsend. She loved him and supported him, prodding her husband not to be hard on his son. Lincoln only read a few books—the Bible, Shakespeare—which he knew very well.

—So what was his first job?

Well, he held odd jobs. As an adolescent, he did odd jobs for his father -- and for other people, his dad pocketing the pay -- but he left home as soon as he could, moving to the small town of New Salem, Illinois. It was there he reputedly fell in love with a woman who was engaged someone else.

–Oooh. Scandal. I love it.

But then she died, and Lincoln became severely depressed—so depressed he stayed in bed for weeks. He had such episodes a lot. Anyway, over the course of his adolescence and young adulthood he worked in a store. He worked at the post office. He made a couple trips down the Mississippi River to New Orleans to deliver goods. That’s when he was introduced to slavery (and was attacked by slaves trying to steal the stuff). Those experiences had a deep impact on him: he emerged from them with a lifelong hatred of slavery, even if, for most of his life, he considered abolitionism impractical.

—So when did he get into politics?

When he was 22 years old, Adam, he ran for the state legislature. He lost. But he got 90% of the votes in his hometown. That was the thing about Lincoln: to know him was to like him. Once, when he was new to town, a friend bragged he could beat the head of the local gang in wrestling. There was a match, and there are two versions of the story. In one, Lincoln won; in the other, he lost. But in both cases, he became lifelong friends with the members of the gang. After he ran for office the second time, he won. He served four terms. Over the course of that time he also taught himself to be a lawyer, passed the bar, and began a legal career. He married a rich woman who also dated Stephen Douglas.

–Oooh. Scandal. I love it.

Hardly, Sadie. But Mary Todd and Lincoln did have a tempestuous relationship, and there are reports of shouting matches that could be heard outside their house. She was difficult, and smart. Mary was from Kentucky, and Henry Clay had been a guest in her home and her father's business partner. Lincoln idolized Henry Clay—he loved the idea of internal improvements, the American System, the whole kit and caboodle. Which was a little hard, because he lived in Jackson country. But Lincoln did pretty well for himself. And by the mid-1840s, he was ready to run for Congress. Here was the problem: there was one district that was reliably Whig, and three guys who wanted the job. So Lincoln proposed they take turns, each supporting the other. His turn came last, and he was indeed elected. But as we discussed, he arrived in Congress for the start of the Mexican War, which he opposed. Not smart. Lincoln didn’t intend to run for re-election, but his stance cost the Whigs the seat. President Fillmore offered him the governorship of the Oregon territory, but Mary nixed that: Siberia. So Lincoln went back to Springfield and got rich. He and Mary had four sons, one of whom died there.

And that’s how things might have ended, if the Kansas-Nebraska Act hadn’t come about.

—Wait. Before you get to that.

Yes, Yin?

—I don’t really understand exactly why Lincoln was so popular. Emily calls him your boyfriend, and you say that people liked him. But I don’t really understand. Can you explain?

Well, that was the point of that wrestling story. And there’s the famous story, you’ve probably heard it, of “Honest Abe” walking miles to refund money to someone he accidentally overcharged by working at the store.

—I still don’t feel I get his personality. We’re told people from history were great and admirable, but I never feel like I understand why.

—It’s true.

I understand. Let me try this. At one point in the 1850s, when Lincoln was a successful, but provincial, lawyer, he was hired by a firm back in New York to represent a manufacturing company for a case that was being tried in Springfield. At the last minute, the case was transferred to Cincinnati. Lincoln was told that, and went there, but he didn’t understand the case would now be handled by a very prominent Cincinnati attorney named Edwin Stanton. Stanton thought Lincoln was a loser, a hick; Stanton’s colleague described Lincoln as “a tall rawly boned, ungainly back woodsman, with coarse, ill-fitting clothing.” Stanton’s crew pushed Lincoln aside during the case, never invited to meet or eat with the other attorneys. When Lincoln was paid for showing up, he returned the check until he was urged to cash it. When he got home, Lincoln described himself as “roughly handled” by Stanton, though he recognized, as many people at the time did, that Stanton was a very talented man, even if he was also a jerk.

A few years later, when Lincoln was president, he fired the corrupt and inept Secretary of War Simon Cameron (Lincoln’s boosters at the Republican Convention of 1860 foisted Cameron on him as the price of the Pennsylvania delegation’s support when he was running for president in 1860). And the man Lincoln chose as his successor? None other than Edwin Stanton, the former Democrat whom he entrusted—wisely—with substantial latitude to run the Civil War. And a few years after that, when Lincoln had been shot and was bleeding to death, it was Stanton who literally stood by him, managing the crisis while he wept. “Now he belongs to the ages,” Stanton said when Lincoln died.

—That’s a really moving story.

I’m glad to you think so, Yin. Does it get at what you’re asking?

—Yes.

There are a lot of stories like it: Lincoln making, and staying, friends with people who disagreed with him. He refused to demonize his opponents. His great rival for the presidency, William Seward, ended up as one of his closest friends. So did one of his adversaries in Congress, abolitionist Charles Sumner—Sumner had been savagely beaten on the floor of Congress after giving a provocative speech against slavery in 1856—who believed Lincoln moved too slowly in abolishing slavery. So did Frederick Douglass, who would also ultimately be an admirer. Lincoln was that kind of guy. He also had a great sense of humor. “God loves ugly people,” he once said in a context of self-deprecation. “That’s why he made so many of them.” (Walt Whitman once wrote that Lincoln was so ugly that he was beautiful.)

But here’s the thing: Lincoln was also a man of great patriotism and moral conviction, and he thought the two went together. He loved his country because he knew it had been very good to him—only in the United States, he plausibly believed, could someone like him be as successful as he’d been—and he hated slavery, not only because it was wrong, but also because it endangered the very idea of what we would call the American Dream. This may be why Lincoln seemed utterly galvanized by Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act, which created the potential for slavery—something he always believed would die—to spread in the name of democracy. Lincoln’s denunciations attracted a lot of attention, and after the Whig Party fell apart and he became a Republican, there was talk of him running for Senate in 1855. But he stepped aside for the sake the party, which was seeking antislavery Democratic support by running another candidate instead. This was another act that won him admirers (and which would eventually pay off).

—So what happened next?

Lincoln remained in the public light in Illinois and around the Midwest. And when Stephen Douglas was up for re-election, Republicans coalesced around him. Everybody knew he was a long shot, which is why there was some talk of actually nominating Douglas as a Republican in the hope they could gain some concessions from him. Everybody but Lincoln, that is.

—Really?

Well, I’m exaggerating a bit. But Lincoln and Douglas went back a long way. Douglas was born in Vermont, and came to Springfield as a young man, just as Lincoln did. They were both excellent lawyers and politicians. Douglas had left Lincoln in the dust—Congressman, Senator, future president. But he knew Lincoln was good.

Lincoln also knew he was a long shot, and he played to Douglas’s vanity: he challenged him to a series of debates around Illinois. Douglas should have said no, and knew he should have said no: front-runners don’t give rivals chances to face them as equals on a stage. But Douglas couldn’t resist, and what followed was one of the truly legendary battles in American political history: the Lincoln-Douglas debates. If we had more time, we’d go into more detail. Suffice it to say that contrary to what is sometimes suggested, they weren’t exactly high-minded affairs. Lots of repetition and innuendo. Lincoln depicted Douglas as a cynic whose indifference toward slavery was dangerous, and Douglas depicted Lincoln as a raging abolitionist. Question: How are senators chosen in 1858?

—The same way they are now?

Nope. What does the Constitution say? How was it done until the Seventeenth Amendment in 1916?

—Oh c’mon, Mr. K. You don’t actually expect us to know that.

Hey, you can’t blame a guy for trying. They’re chosen by state legislatures. And how are state legislatures chosen? In part by the census. In 1858, Illinois is working off the 1850 census. And in 1850—but not by 1860—the population of Illinois is mostly in the southern part of the state. That part of the state has more weight, and so Douglas wins. Lincoln says he feels like the boy in Kentucky who stubs his toe while rushing to visit his girlfriend: it hurts too much to laugh, but he’s too old to cry.

—So how does he become president, then?

Well, Jonah, that’s a long story—a longer story than I can tell in a course like this. Suffice it to say that even though Lincoln loses, the Senate race attracts national attention. Lincoln is by no means a household name, but the people who are household names—Douglas for the Democrats, Seward for the Republicans—are too controversial to be easily elected. When the Democrats hold their convention in Charleston in 1860, the proslavery wing walks out in protest at the prospect of Douglas getting the nomination; they nominate their own candidate. The Douglas crowd reconvenes in Baltimore and nominates him there. The Republicans happen to have their convention in Lincoln’s backyard, Chicago. He and his supporters skillfully position him as everybody’s safe second choice, and that works like a charm. So now there’s Douglas, and the proslavery candidate, whose name is John Breckinridge, and Lincoln, and a fourth candidate, John Bell of Tennessee, who runs as a “constitutional unionist,” which basically means anything to avoid a war. Under such circumstances, Lincoln is a cinch to win.

Lincoln’s position is clear but firm: he won’t attack slavery where it exists, but won’t allow it to expand. All through the fall, there are indications that the proslavery crowd finds this unacceptable, that they’ll leave the Union if he gets elected. Not a lot of people believe them, though. Lincoln doesn’t either. He gets 39% of the vote: more than anyone else but hardly a majority. A few weeks later, the South Carolina legislature votes to leave the Union.

—Oh my, Mr. K.! What will your boyfriend do?

Next: Essaying